I’ve read the book, I’ve read the books about the book, I’ve seen the movie adaptation, and now I have had the pleasure of seeing the holiest of holies of the Beat Generation – the original manuscript of Jack Kerouac’s novel, ‘On The Road’.

Written over a period of three weeks in April 1951, the manuscript takes the form of a 120-foot-long scroll comprised of sheets of tracing paper which Kerouac stuck together in order to prevent his creative flow being interrupted by having to stop and feed individual pages into his typewriter.

This almost mystical piece of contemporary literary history is on display to the public at the British Library, the first 50-feet of it unfurled, in a specially-constructed case until 27 December 2012.

This almost mystical piece of contemporary literary history is on display to the public at the British Library, the first 50-feet of it unfurled, in a specially-constructed case until 27 December 2012.

The scroll is on loan from the collection of James S Irsay, who bought it at auction in 2001 for $2.43 million (£1.5 million), the highest sum ever paid for a literary manuscript. It is the first time it has been displayed in London.

The exhibition includes a who’s who of the key figures of the Beat Generation, first editions of classic Beat books from the Library’s own collection, photographs by Allen Ginsberg, and rare sound recordings of Kerouac, Ginsberg and William Burroughs. It coincides with the release this month of Walter Salles’s film adaptation of ‘On The Road’, starring Garrett Hedlund (Dean Moriarty aka Neal Cassady), Sam Riley (Sal Paradise aka Kerouac), Kristen Stewart (Marylou) and Kirsten Dunst (Camille).

I was lucky enough to see the film’s UK premiere on August 16 at the Sommerset House outdoor summer screen.

Without going into full review mode, I will say that I thought it to be as good a job as can probably be expected of condensing the verbosity and intensity of the book into the limitations of the film format. And it did succeed in stirring a feeling of wanderlust in my belly, just as the book always does.

Upon entering the British Library I was filled with a child-like excitement at the prospect of finally seeing the original manifestation of the book which has been so influential to so many generations, and which has directly inspired me on multiple occasions to get in my car and just go.

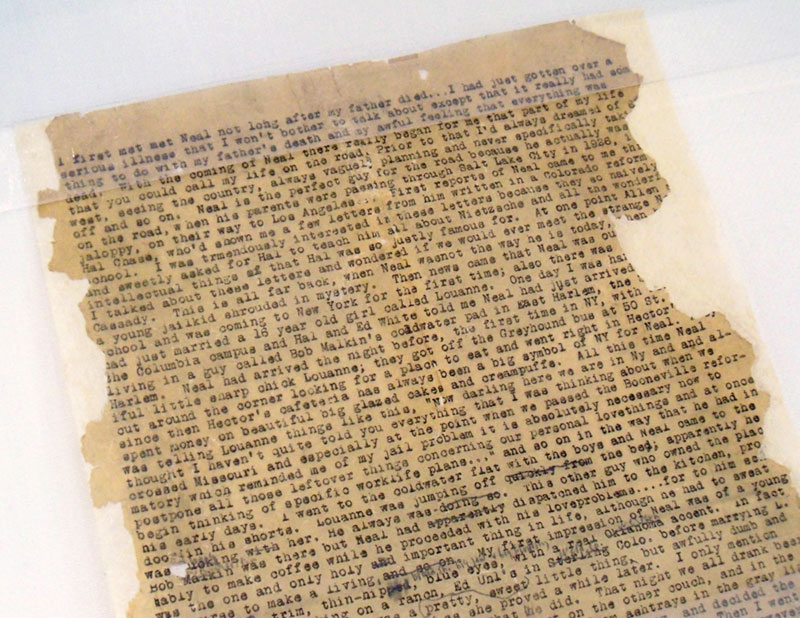

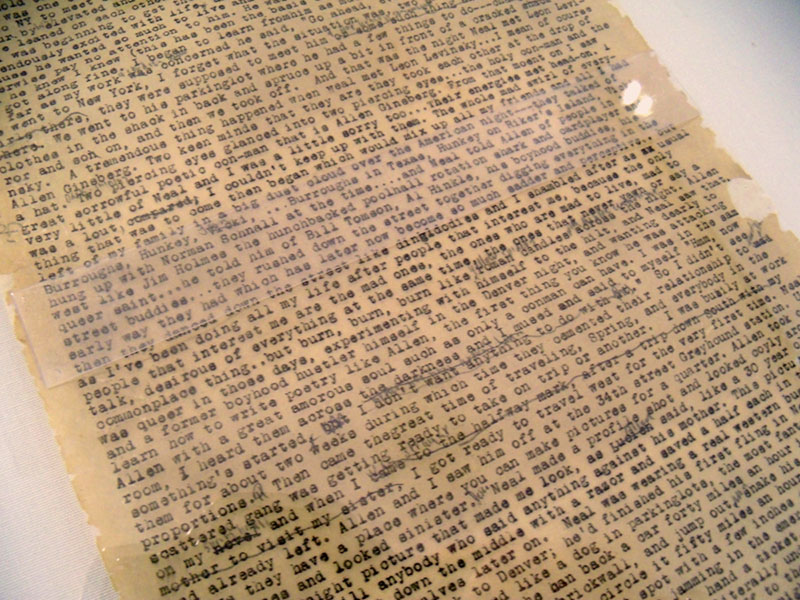

The scroll, browned with age and ragged at the edges in some places, is typed without paragraph breaks. It is testament to the vision I have of Kerouac’s manic, stream of consciousness style of writing, which he called “spontaneous prose”.

Just as Dean encouraged Sal in the book, Kerouac’s scroll embodies the notion of just “getting it all down without modified restraints and hang-ups on literary inhibitions and grammatical fears”.

About two-thirds of the way down the section of scroll on display there are pencil annotations visible – crossings out, bracketing of passages and paragraphs, sentences circled and arrowed into different places.

The finished novel differs in several ways to the manuscript, including the changing of the real names of Kerouac’s friends to pseudonyms.

For example, the scroll starts: “I first met Neal not long after my father died…” whereas the book begins: “I first met Dean not long after my wife and I split up…”

But the years and revisions between its writing in 1951 and publication in 1957 did not diminish its wild and ecstatic nature, and it remains Kerouac’s most famous work.

‘On The Road’ has been described as not just a literary journey, but a spiritual quest. Call me over-sentimental, but standing in the same room as the scroll, reading the words of one of my favourite books exactly as they were originally typed by one of my favourite authors, I feel as if I’ve completed a sort of pilgrimage of my own.

Photographs of the exhibition and scroll by Amy Freeborn, with permission from James S. Irsay © Estate of Anthony G. Sampatacacus and the Estate of Jan Kerouac. Manuscript text © The Estate of Jack and Stella Kerouac.