Syd Moore has always felt an affinity for witches.

As a child, when her Nan told her fairytales, it wasn’t the princesses Moore aspired to be, “I was always more drawn to the witch characters,” she says.

“The princesses just seemed to hang around, waiting to get married or to be rescued, but the witches were really active. Now I can say that my perception was that they were autonomous, but at the time I just thought: the witches did stuff!”

It’s a trait that’s evident in her own life. Moore counts among her past and present professional roles: publicist, television host, magazine editor, teacher, and arts worker.

A proud Essex girl, born and bred, Moore returned to the county 15 years ago after a stint living in London. Her new Leigh-on-Sea local was called The Sarah Moore, and — narcissistically, she confesses — she wondered if the two might be related.

It turned out there was no familial connection, but there was a kindred spirit. Folklore has it that Sarah Moore was a “sea witch”. A notorious figure in the 19th Century, she allegedly held the fate of sailors in her hands thanks to a magical command of the winds. But by the late 20th Century she was mostly forgotten by the locals.

“The legend goes that she used to sit on Bell Wharf and would ask sailors for a penny. If they gave her one she’d bless them with a good wind,” Moore explains.

Another local pub, Ye Old Smack, is named after a ship whose captain is said to have forbade his sailors from giving Sarah Moore any money. In retaliation, she allegedly punished him by conjuring the Great Storm of the Estuary.

The story goes that The Smack was caught in the storm, and the captain was forced to cut down the ship’s mast, which he did with three strikes of an axe. As the mast hit the deck, the storm eased. When the crew returned safely back to Bell Wharf, they found the body of Sarah Moore, dead from three axe wounds.

An alternative ending says that The Smack’s crew were lost in the storm and the captain, the sole survivor, swore vengeance on the sea witch. The next day her headless body was going floating in Doom Pond, or the Drowning Pool, which, the contemporary Moore, says, “is just around the corner from where I live.”

Fascinated by the legend, Moore set out to investigate further. She added published author to her list of professional achievements when her debut novel, ‘The Drowning Pool’, was released in 2011. It’s a ghost story that mixes historical fact and folklore with contemporary fiction and features a protagonist who shares her name with a sea witch.

Moore’s research (along with inspiring more books) also resulted in a revelation: of Essex’s past as “Witch County” and the continued — if not persecution, then certainly vilification — of its women.

“I came across a statistic, which is, that between 1560 and 1680 in Hertford, Surrey, and Sussex there were 185 indictments of witchcraft. But for the same period of time, Essex on its own had 503, that we know of, which is huge. I was really shocked by that.

“On one day in 1645 in Chelmsford there were 19 women put to death. Compare that to Pendle, where there was 10, but over a period of a few month. And Salem, where there was 20, but over 15 months. This was just one day in Essex!

“Being a feminist and woman of Essex, I couldn’t believe that I hadn’t heard about this before. That’s when I started digging in much more detail.”

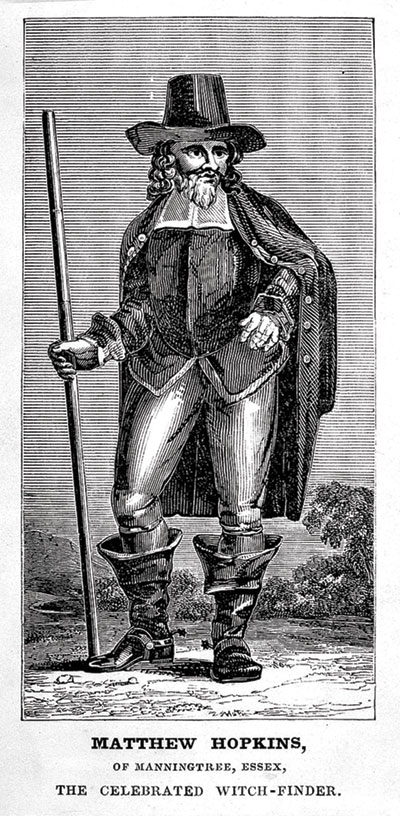

That digging uncovered a commonality among the majority of Essex’s accused witches: “They were mostly poor, so therefore at the low end of the social scale. They were also called ‘loose’, which at the time meant they were not under the protection or shelter or control of a man, because — certainly in the era of Witchfinder General Matthew Hopkins — a lot of the men were away fighting in the civil war. And because they didn’t have a man to speak for them in court, they were considered legally ‘dumb’.”

Moore — whose “twin obsession” is the Essex Girl stereotype — says something suddenly “clicked”.

“What if these centuries-old feelings of dismay and revulsion for the women of Essex never actually went away? It’s my theory that, despite memories of the witch hunts fading, the reputation of the county’s women never really recovered.”

The modern-day Essex Girl — and the “knee-jerk” characterisation of her as all glamour, dim wit, and loose morals — bears a striking resemblance to the Essex women who were drowned, tortured, and hanged 400-odd years ago, Moore realised.

It was after the enthusiastic response to an International Women’s Day talk she delivered on the correlation, that Moore’s mission to “re-brand” the Essex Girl coalesced into the formation of the Essex Girls Liberation Front.

The Essex Girls Liberation Front

She had already been chipping away at the task for a few years. From her 2011 collaboration with artist friend Heidi Wigmore on the Top Trumps-style game, Super Strumps: “We gave all these stereotypes a magical quality, so the Essex Girl was invulnerable to cold, the career woman could penetrate glass ceilings…” To her on-going work in schools highlighting to children the number of forgotten luminaries that have hailed from their county: “Anne Knight was the first person to write a pamphlet about women’s suffrage, about 100 years before anyone else, and was also a very, very active campaigner against slavery, and has a town in Jamaica named after her — she’s from Chelmsford and people don’t know about her.”

The fledgling aims of the Essex Girls Liberation Front is to turn the stereotype into “something that is positive”, which Moore says, “in this day and age, to be sexually autonomous, to know what you want, to avoid being manipulated, really is a positive thing”.

Despite what the Oxford English Dictionary says — and the failed 2016 campaign to remove its definition of ‘unintelligent, promiscuous, and materialistic’ — Moore is determined to show the Essex Girl for what she really is: “enterprising, bold, sassy”. She is not defined by her hair colour, skin colour, skirt length, or heel height, but by her state of mind, her state of being.

In the meantime, “the jury is still out” on what exactly it was about Essex in the 15th and 16th centuries that made it such a hotbed for witch hunters, and earned it the nickname of “Witch County”. Theories around the dissolution of monasteries, land enclosures, and remoteness abound.

None of these quite satisfy Moore, who — while admitting that “a lot more research has to be done” — does offer a consequence of the intense activity, if not a definitive cause: “the scapegoating of women”.

Almost without exception, Moore says, victims were the old and the poor, or the unwed mothers, who received support from the local parish via taxes levied against the rest of the community, and therefore were a financial burden. They were the healers who recommended herbs which successfully, ‘magically’, alleviated various ailments, and therefore were just as capable of magically making crops fail.

“Witch hunts were about superstition and scapegoating and bullying, and it’s really important to remember that the victims of the witch hunts were just that: victims,” she says

“What you find is that there is a grain of truth to the underlying story, but the witch aspect has been elaborated.

“Take Sarah Moore — a real woman, an ordinary woman, who’s buried in St Clements churchyard in Leigh on Sea — the Great Storm of the Estuary occurred in 1870, but she died in 1867, so she couldn’t possibly have raised it. It’s just been conflated with her. She’s been scapegoated for ordinary phenomena.”

In her writing, as in her advocacy, Moore is determined to set the record straight about the women and girls of Essex.