When people are asked about their favourite smells, very often the answer is something associated with their childhood.

For Cecilia Bembibre, who grew up in rural Argentina, what immediately comes to her mind is “the smell of the harvester, the smell of the animals”.

“Still today those smells are comforting to me,” she says. “It sounds very weird, because out of context, they might not be pleasant smells, but memory’s a funny thing.

“It doesn’t mean I want to wear (those rural smells) as a perfume, but sometimes when you’re in a strange place and you get a wiff of that, it becomes immediately familiar.”

It’s that sense of familiarity, that connection between smell and place and identity, which Bembibre deals with in her work at University College London. Her research in the heritage science laboratory is concerned with the identification of smells that might have cultural value, and the archiving of those smells as a form of cultural heritage preservation.

Cecilia Bembibre sampling the scent of a book, image by National Trust/James Dobson

“Smells impact the way we think, behave and feel, they also trigger personal memories and can be related to a feeling of identity, and yet there is no strategy in the UK to study and protect our olfactory heritage,” she explains.

Her project, ‘The Smell of Heritage’, sprang from on-going study about the way certain smells — or more accurately, the chemicals responsible for them: volatile organic compounds — could be related to material changes in historic objects, and thus inform the preservation of that object.

“We decided to expand this study to complement the knowledge on the chemical composition of smells with information about the way people perceived it, including ways to describe the aroma, rating its intensity and recording how pleasant it is to the people who smell it,” Bembibre says.

“Since smells had not been yet studied systematically in the context of heritage, we developed a framework to identify smells that might have cultural value, analyse them chemically and from the sensory viewpoint, and document that information so the smell could be preserved.

“When we wanted to do a first case study to test the framework, we were looking for a smell that had significance to many people and carried historic information.”

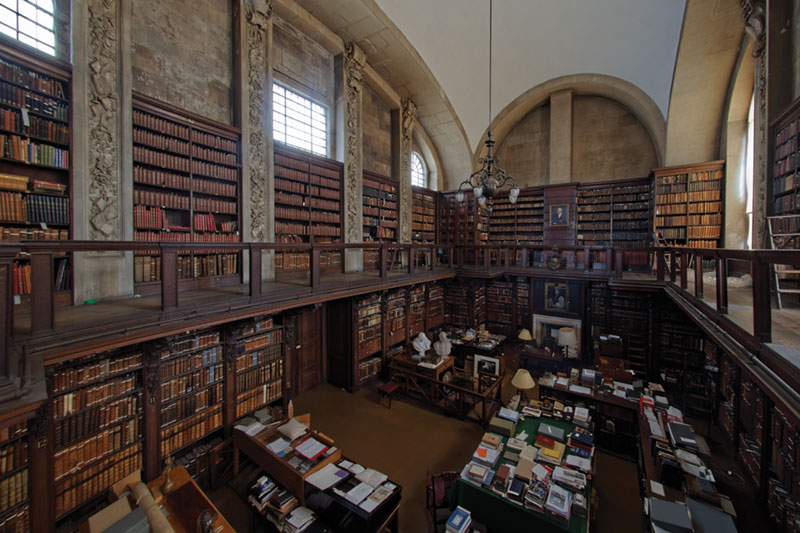

The candidate? Books in the libraries of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral and the Kent country estate, Knole House.

St Paul’s Cathedral

“The smell of old books and historic libraries was an ideal example, because there is quite a bit of evidence that we relate this aroma to knowledge, a pleasurable sensory experience, and personal memories.”

What came out Bembibre’s research was an ‘odour wheel’ that correlated the chemical composition of a scent with the human, or sensory, interpretation of it.

So, when people thought they smelled chocolate or coffee when sniffing old book samples, “it makes sense from a chemical point of view, because coffee and chocolate come from fermented or roasted natural lignin- and cellulose-containing products, and they share many volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with decaying paper,” Bembibre explains.

What comes next for Bembibre is determining how this and future odour wheels, as well as smell samples, can be archived for posterity.

“At the moment I am looking at what’s out there and what form they take. There are a few smell archives — private collections, artists who have come up with their own way of collecting smells in little pots and labelling them, and I’m looking at what institutions like the Osmothèque in Paris, which archives historic perfumes, have done.”

Osmothèque in Paris

Once the criteria for a heritage smells archive has been established, that decisions on what goes into it should be made not just by scientists, but by ordinary citizens.

“I’m very curious to see what people in the UK might choose for smells that are important to them. Instead of us deciding in the lab what will be the next smell to analyse, I want to ask people for their stories, their memories, their choices, and make it a discussion to describe our olfactory heritage.”

She cites several previous efforts in this area as possible ways forward.

In 2001 the Japanese Ministry for the Environment invited residents to vote for locations where they valued the smell, creating a final list of ‘100 most fragrant’ places.

“The places they chose ranged from temples that smell of incense, to commercial streets that might smell of fumes, secondhand bookshops, saki distilleries. And these places are now protect with policy — and promoted as a special type of tourism — to ensure that these places are going to be passed down to future generations as they are today, or with very little change.

“The project also recorded a lot about the people that chose the places and the reasons why they were chosen.”

Closer to home, Victoria Henshaw from the University of Sheffield did a lot of research into ‘urban smellscapes’, and Kate McClean from the Royal College of Art, has created ‘smellmaps’ of various cities around the world.

“Both of them recorded how the identity of a place can be very, very closely linked to a smell. For example, there was a neighbourhood that had a tea factory, and the company decided to relocate abroad, and when that disappeared the community felt it had lost a sense of identity.”

At the heart of Bembibre’s project is the desire to ensure those smells, those olfactory indicators of cultural identity, are recorded and protected, for our own, as well as history’s sake.

“Smells can be fundamental in shaping who we are and where we belong. In the heritage context, experiencing what the world smelled like in the past enriches our knowledge of it, and, because of the unique relation between odours and memories, allows us to engage with our history and our culture in a more emotional way.”