Behind the Scenes at the Natural History Museum, London

When the naked models for the Musuem’s Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story exhibition were unveiled earlier this year, there were a few sniggers – from staff and visitors alike – at their state of undress. But Ned the Neanderthal and Quentin the Homo sapiens are not the first men to get their bits out in the Museum’s galleries.

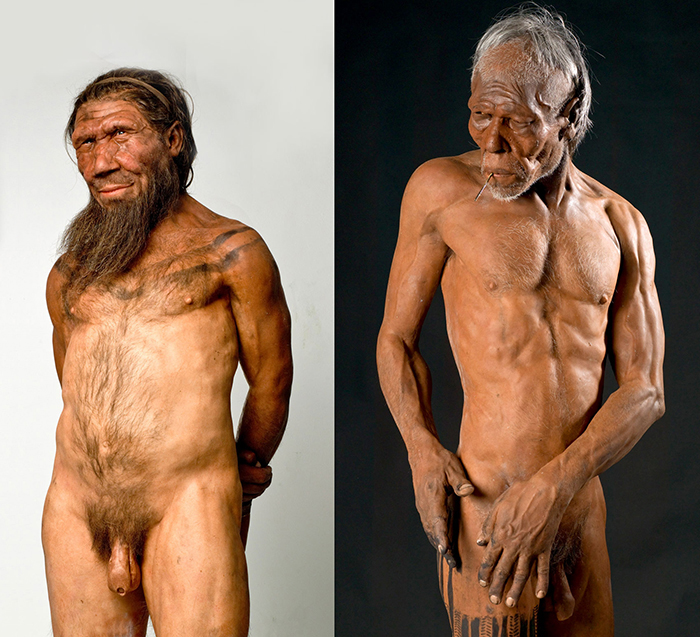

Ned (left) and Quentin (right) let it all hang out for science, © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

Back in 1900, Edwin Ray Lankester, Curator of Molluscs and Director of the Natural History Department of what was then the British Museum, requested the funds to commission a plaster cast of Prussian-born strongman and bodybuilder Eugen Sandow, who would pose fully-flexed and in all his glory.

Although perhaps a strange idea at first thought, Lankester argued that the statue would provide a perfect example of European man (he intended to get a series of statues made to illustrate different nationalities). He said it would be: “A striking demonstration of what can be done in the way of perfecting muscles by simple means (and) hand down to future generations the most perfect specimen of physical culture of our day, perhaps of any age.”

Eugen Sandow (1867-1925) had been inspired as a teen by classical Roman statues of athletes and deities, and dedicated himself to obtaining the ‘perfect physique’. He is credited as the ‘father of modern body building’ for successfully making the move from Victorian strongman to bona fide muscle-bound businessman and celebrity.

Sandow patented his own dumbbells, set up personal fitness schools and a monthly fitness magazine, designed exercise regimes and published books. He counted kings Edward VII and George V, as well as the likes of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, James Joyce, William Butler Yeats and Thomas Edison, among his adherents.

Edison invited Sandow to strut and flex – or, as it was described at the time, ‘perform a series of tableaux vivants’ – for use in his pioneering kinetoscope motion picture viewing device.

Lankester’s request for the Sandow statue was approved by the Museum’s Board of Trustees and a company in Covent Garden was instructed to make it, at a cost of £55. Sandow’s body was cast in small sections, and it was required that he hold his muscles at ‘full strain’ for around 15 minutes at a time while the plaster set. In a 1939 edition of Iron Man magazine, Sandow said of the process:

“I should like to say that I regard it as the greatest feat of endurance I have ever performed. The strain was awful. One feels as if he is being suffocated, especially when the mould of the face is being taken. I am told that only about one man in two hundred can stand having their face done and I am not a bit surprised.

“But if that is the case I don’t believe that one in a million could stand to have his chest done, in the trained position. I had to keep the muscles of the chest and abdomen still while tensed and take very small quick breaths, never entirely filling or emptying the lungs, but just taking in enough fresh air to take the place of what I used up, and at the same time keeping the muscles set so as not to disturb the contour or the plaster.

“Of course I was only too glad and proud to do it. I grudge no trouble and time in the cause of physical culture. However, I don’t think I’d go through with it again for any amount of money.”

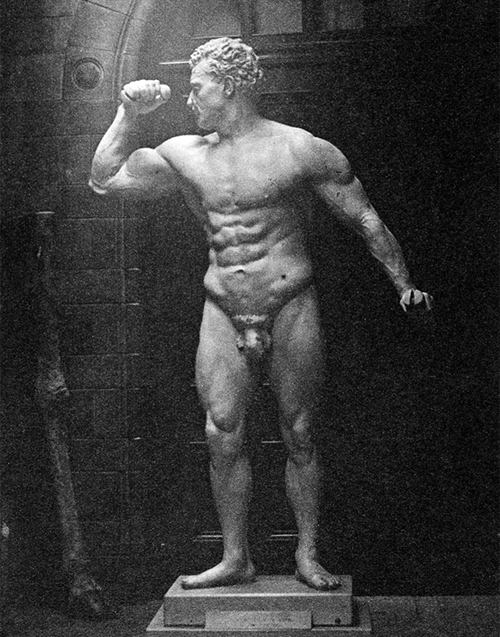

The Eugen Sandow statue on display in 1901, in what is now known as Dinosaur Way, © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

The finished Eugen Sandow statue was delivered to the Museum on 18 July 1901 and went on public show shortly after.

But Sandow’s reign as the personification of physical magnificence in the Museum was to be very short-lived. Less than three months after the statue made its debut, one of the Museum’s Trustees, Lord Walsingham, complained that it was too offensive, even after a fig leaf had been placed over the private parts. Alas, the Board agreed, and on 26 October 1901 the statue of Sandow was forever relegated to deepest, darkest storage.

However, the story doesn’t end there. In the early 1990s the Museum received a request to make a copy of our statue, from none other than Arnold Schwarzenegger. The former Mr Universe wanted a Sandow of his own for his private bodybuilding memorabilia collection.

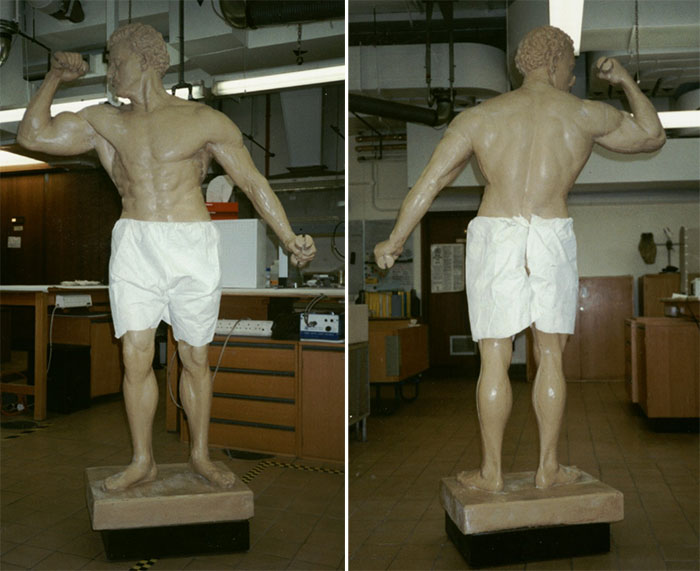

Then-Museum conservator Nigel Larkin was assigned to the task. He said: “I had to put the statue back together, fake up the joins and then I made a two-part mould around it from silicon rubber and fibreglass. (The copy) was relatively light, compared to the original plaster version, which was very heavy. It was all in one piece and stood over six feet tall, with the base.

“It was quite unusual to do a model of something so large. It was much bigger than even most dinosaur limb bones. And it wasn’t cylindrical, he’s got his arm sticking out… It was quite sophisticated and something I’m quite proud of.”

Author David Waller, who in 2011 wrote the book ‘The Perfect Man: The Muscular Life and Times of Eugen Sandow, Victorian Strongman’, said of his visit to see the statue in storage at the Museum:

“It is the closest one will ever come today to Sandow’s body as seen by his contemporaries and, despite the chipped plaster and other imperfections, one cannot but be impressed by the ochre-coloured form. He is neither tall, nor over-developed in the freakish manner of the modern body-builder.

“The waist is trim and the muscles of the legs and chest are exceptionally well-defined and one gets a decided impression of the power if not the beauty that made such an impact on his contemporaries. The head turns insouciantly to one side and one is struck by the immaculately preserved moustache and by his shocking nakedness.”

The Eugen Sandow model, briefly reassembled and photographed in 1981, © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London